OUR HISTORY

Christ for the World Chapel began ministry at JFK Airport in 1964 as the JFK Protestant Chapel.

The ministry was established by the Council of Churches of the City of New York (then, The Protestant Council). Housed in a stunning A-frame structure designed by renowned architect Edgar Tafel, a protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Chapel was set between Our Lady of the Skies Roman Catholic Chapel and the International Synagogue at the JFK Tri-Faith Plaza.

While the three chapels together in the Plaza provided a picturesque setting for weddings and a convenient location for community and church meetings, the location was not particularly convenient for passengers or employees who were faced with a daunting journey on foot across two interstate highways.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey proposed including the chapels in the JFK 2000 project as it was first proposed in the early 1980s. The last service in the old chapel was held January 1, 1988, closing with a congregational procession carrying liturgical artifacts to the new interim Interfaith Chapel located in the International Arrivals Building.

Not only was the interim chapel more accessible to employees and passengers, but the arrangement provided the opportunity for closer collaboration among the three chaplains, leading to a stronger interfaith religious presence in the Airport community.

In May 2001, the new Terminal 4 opened, replacing the International Arrivals Building. Today, four chapels stand side by side in testimony of our mutual commitment to an interfaith religious presence and cooperation at America’s Gateway to the World.

The ministry was established by the Council of Churches of the City of New York (then, The Protestant Council). Housed in a stunning A-frame structure designed by renowned architect Edgar Tafel, a protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Chapel was set between Our Lady of the Skies Roman Catholic Chapel and the International Synagogue at the JFK Tri-Faith Plaza.

While the three chapels together in the Plaza provided a picturesque setting for weddings and a convenient location for community and church meetings, the location was not particularly convenient for passengers or employees who were faced with a daunting journey on foot across two interstate highways.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey proposed including the chapels in the JFK 2000 project as it was first proposed in the early 1980s. The last service in the old chapel was held January 1, 1988, closing with a congregational procession carrying liturgical artifacts to the new interim Interfaith Chapel located in the International Arrivals Building.

Not only was the interim chapel more accessible to employees and passengers, but the arrangement provided the opportunity for closer collaboration among the three chaplains, leading to a stronger interfaith religious presence in the Airport community.

In May 2001, the new Terminal 4 opened, replacing the International Arrivals Building. Today, four chapels stand side by side in testimony of our mutual commitment to an interfaith religious presence and cooperation at America’s Gateway to the World.

The annual Aviation Industry Awards Luncheon, begun in 1972 to help support the Protestant Chapel at JFK Airport, was named in honor of Bishop Milton Wright. The Luncheon is held annually in the Spring and recognizes outstanding leaders in the aviation industry.

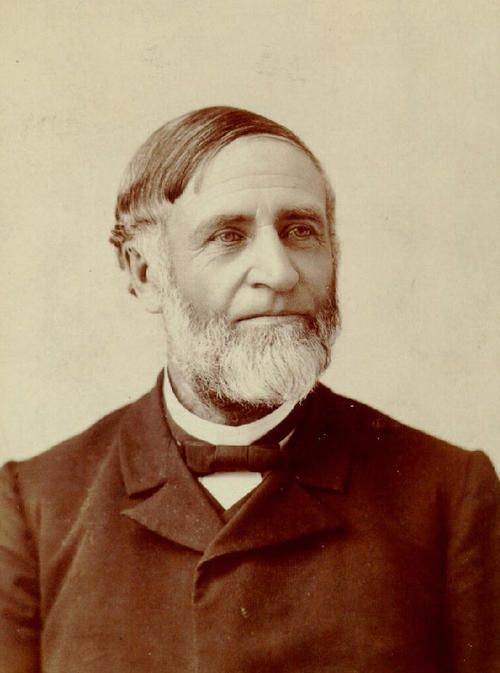

Bishop Milton Wright, the father of the famous “Wright Brothers” – Orville and Wilbur – was pastor of a church in Dayton, Ohio. He served as a bishop in the Church of the Brethren for 24 years and taught in a college for two years. When Wilbur was eleven and Orville seven, their father gave them a ready-made fluttering toy, of no practical use on earth. It cost only a few pennies but it was amusing to watch this little man-made gadget make like a humming bird.

The principle was simple enough: a twisted rubber band that counter-rotates a couple of light paddle-wheels in horizontal planes, catching the air and throwing it downward, The machine is thereby pushed upward with God’s law of equal and opposite reactions – which Mr. Newton had thoughtfully formularized. The boys learned its lesson well. They were both apt students, with phenomenal memories, like their father’s.

Without either having graduated from high school, they opened a bicycle repair shop in Dayton, Ohio. They had to hold their own against 18 local bicycle makers and dealers, six repair shops, one tire maker and one specialist enameller. They started manufacturing bicycles from scratch and marketing them as “Wright Flyers.” The partnership prospered mightily. Together they looked around for life’s neat opportunity. Quietly, these two lonely, self-educated mechanics resolved to build the world’s first man-carrying flying machine. And from that moment until success was assured six years later, neither Wilbur nor Orville wavered one degree from their determined course to make workable wings for men.

Bishop Wright encouraged and supported his sons in their ambition to fly. He said, “As has been attested by many witnesses, I saw Orville fly one day twenty-one miles in thirty-three minutes (10-4-1905). The next day I saw Wilbur fly twenty-four miles in thirty-eight minutes. They flew at less than 65 feet altitude.”

In Who’s Who in America, Orville is listed as a “Machinist Inventor” and Wilbur as a “Machinist Aeronaut.”

Bishop Milton Wright, the father of the famous “Wright Brothers” – Orville and Wilbur – was pastor of a church in Dayton, Ohio. He served as a bishop in the Church of the Brethren for 24 years and taught in a college for two years. When Wilbur was eleven and Orville seven, their father gave them a ready-made fluttering toy, of no practical use on earth. It cost only a few pennies but it was amusing to watch this little man-made gadget make like a humming bird.

The principle was simple enough: a twisted rubber band that counter-rotates a couple of light paddle-wheels in horizontal planes, catching the air and throwing it downward, The machine is thereby pushed upward with God’s law of equal and opposite reactions – which Mr. Newton had thoughtfully formularized. The boys learned its lesson well. They were both apt students, with phenomenal memories, like their father’s.

Without either having graduated from high school, they opened a bicycle repair shop in Dayton, Ohio. They had to hold their own against 18 local bicycle makers and dealers, six repair shops, one tire maker and one specialist enameller. They started manufacturing bicycles from scratch and marketing them as “Wright Flyers.” The partnership prospered mightily. Together they looked around for life’s neat opportunity. Quietly, these two lonely, self-educated mechanics resolved to build the world’s first man-carrying flying machine. And from that moment until success was assured six years later, neither Wilbur nor Orville wavered one degree from their determined course to make workable wings for men.

Bishop Wright encouraged and supported his sons in their ambition to fly. He said, “As has been attested by many witnesses, I saw Orville fly one day twenty-one miles in thirty-three minutes (10-4-1905). The next day I saw Wilbur fly twenty-four miles in thirty-eight minutes. They flew at less than 65 feet altitude.”

In Who’s Who in America, Orville is listed as a “Machinist Inventor” and Wilbur as a “Machinist Aeronaut.”

- Edited excerpts from The Bishop’s Boys by Dallas Sherman; Flying Machine, December 1959; and from Wright Reminiscences by Ivonette Wright Mil

Bishop Milton Wright

The annual Aviation Industry Awards Luncheon, begun in 1972 to help support the Protestant Chapel at JFK Airport, was named in honor of Bishop Milton Wright. The Luncheon is held annually in the Spring and recognizes outstanding leaders in the aviation industry.

Bishop Milton Wright, the father of the famous “Wright Brothers” – Orville and Wilbur – was pastor of a church in Dayton, Ohio. He served as a bishop in the Church of the Brethren for 24 years and taught in a college for two years. When Wilbur was eleven and Orville seven, their father gave them a ready-made fluttering toy, of no practical use on earth. It cost only a few pennies but it was amusing to watch this little man-made gadget make like a humming bird.

The principle was simple enough: a twisted rubber band that counter-rotates a couple of light paddle-wheels in horizontal planes, catching the air and throwing it downward, The machine is thereby pushed upward with God’s law of equal and opposite reactions – which Mr. Newton had thoughtfully formularized. The boys learned its lesson well. They were both apt students, with phenomenal memories, like their father’s.

Without either having graduated from high school, they opened a bicycle repair shop in Dayton, Ohio. They had to hold their own against 18 local bicycle makers and dealers, six repair shops, one tire maker and one specialist enameller. They started manufacturing bicycles from scratch and marketing them as “Wright Flyers.” The partnership prospered mightily. Together they looked around for life’s neat opportunity. Quietly, these two lonely, self-educated mechanics resolved to build the world’s first man-carrying flying machine. And from that moment until success was assured six years later, neither Wilbur nor Orville wavered one degree from their determined course to make workable wings for men.

Bishop Wright encouraged and supported his sons in their ambition to fly. He said, “As has been attested by many witnesses, I saw Orville fly one day twenty-one miles in thirty-three minutes (10-4-1905). The next day I saw Wilbur fly twenty-four miles in thirty-eight minutes. They flew at less than 65 feet altitude.”

In Who’s Who in America, Orville is listed as a “Machinist Inventor” and Wilbur as a “Machinist Aeronaut.”

Bishop Milton Wright, the father of the famous “Wright Brothers” – Orville and Wilbur – was pastor of a church in Dayton, Ohio. He served as a bishop in the Church of the Brethren for 24 years and taught in a college for two years. When Wilbur was eleven and Orville seven, their father gave them a ready-made fluttering toy, of no practical use on earth. It cost only a few pennies but it was amusing to watch this little man-made gadget make like a humming bird.

The principle was simple enough: a twisted rubber band that counter-rotates a couple of light paddle-wheels in horizontal planes, catching the air and throwing it downward, The machine is thereby pushed upward with God’s law of equal and opposite reactions – which Mr. Newton had thoughtfully formularized. The boys learned its lesson well. They were both apt students, with phenomenal memories, like their father’s.

Without either having graduated from high school, they opened a bicycle repair shop in Dayton, Ohio. They had to hold their own against 18 local bicycle makers and dealers, six repair shops, one tire maker and one specialist enameller. They started manufacturing bicycles from scratch and marketing them as “Wright Flyers.” The partnership prospered mightily. Together they looked around for life’s neat opportunity. Quietly, these two lonely, self-educated mechanics resolved to build the world’s first man-carrying flying machine. And from that moment until success was assured six years later, neither Wilbur nor Orville wavered one degree from their determined course to make workable wings for men.

Bishop Wright encouraged and supported his sons in their ambition to fly. He said, “As has been attested by many witnesses, I saw Orville fly one day twenty-one miles in thirty-three minutes (10-4-1905). The next day I saw Wilbur fly twenty-four miles in thirty-eight minutes. They flew at less than 65 feet altitude.”

In Who’s Who in America, Orville is listed as a “Machinist Inventor” and Wilbur as a “Machinist Aeronaut.”

- Edited excerpts from The Bishop’s Boys by Dallas Sherman; Flying Machine, December 1959; and from Wright Reminiscences by Ivonette Wright Mil